This scientist has spent more than 20 years studying the parasite that causes malaria.

Jake Baum, Professor of Infectious Diseases and Head of School for Biomedical Sciences, has dedicated his entire career to malaria. His research has taken him from London, to Melbourne, back to London and now UNSW Sydney. Originally from the UK and now an Australian citizen, he refers to himself as a “ping-pong Pom”.

Art versus science

Growing up in Bristol in the UK, Jake had a balance of influences between art and science.

“My late father was a paediatrician and did research in child health, and my mum is an abstract painter.

“I’m one of four brothers. Two of us became scientists and the other two are artists. We’re a perfect genetic cross!” he said.

Jake and his brothers, enjoying a family walk in the West Country just outside of Bristol.

Before pursuing a career in science, there was a moment when Jake almost chose music. Captivated by the mysteries of genetics and biology, he instead turned his attention to a very different rockstar journey – biomedical science.

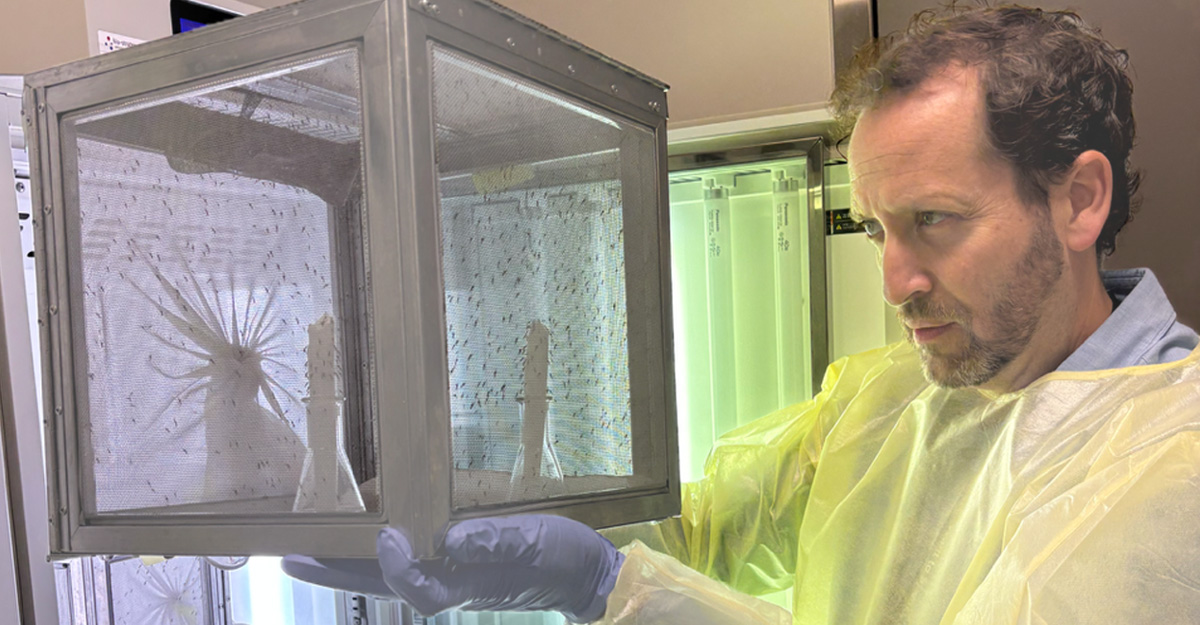

Today you’ll find him in the Baum lab, where he’s dedicated the last three years to establishing a UNSW insectary to better understand the parasites that cause malaria.

World Malaria Day 2025

Each year Jake’s team acknowledges World Malaria Day on 25 April. At Imperial College London, they’d put a giant inflatable mosquito on top of buildings for public outreach.

Jake says that this year “feels particularly poignant”.

A child dies every minute from malaria. In 2022 and 2023 the World Health Organization [WHO] approved the first licensed vaccines against this disease. Jake said these are now being rolled out in Africa, while at the same time, the US is cutting a significant amount of funding for global health.

“Suddenly support from economically wealthy countries that has been instrumental in reducing deaths from infectious diseases in low to middle income countries, is in doubt. So, ironically at this key moment of hope with new vaccines, tools and the potential to turn the tide on malaria we also have the specter of unimaginable despair in global health,” he said.

A disease that shouldn’t exist

Jake’s interest in malaria began at Oxford. He thought he’d deep-dive into sequencing the human genome until his PhD supervisor introduced him to this most-ancient human disease.

To contextualise his research, he took a field trip to the Gambia in West Africa. Seeing children affected by malaria drove his passion to spend the next two decades studying the parasite.

“It’s a disease that shouldn’t exist, but it still does because of poverty, nations at war and poor health infrastructure,” he said.

Jake believes that malaria is “an economic handbrake holding many African countries back from growth.

“There’s a very strong dotted line between health, education, infrastructure and conflict. It may sound like a long shot, but I think getting rid of diseases like malaria would legitimately make the world a more peaceful place,” he said.

The UNSW mosquito insectary

Establishing an insectary at UNSW was paramount for Jake.

“Malaria parasites have a complex life cycle alternating between mosquitoes and humans. Most researchers only specialise on one stage. Indeed, before I moved to London, I was intensely focused only on the blood (human) stages,” he said.

This all changed during his time at Imperial College London, where, with access to the entire life cycle, a postdoctoral scientist “completely transformed the lab’s world view” and got Jake thinking about vaccines, in particular those that stop infection.

“Despite the WHO’s work in the last few years, we still don't have a vaccine that works well enough. It's taken 50 years to license the current ones, but these are only 50-60% effective. Don’t get me wrong, they are transformational, but if we really want to eradicate malaria, we need vaccines that are potent and last a long time. For this, we will need to think across the life cycle of the parasite.

“With a UNSW insectary and our research program now live, we have a chance to produce something that really might have an impact on malaria in the long run,” he said.

Can you tell us something about you that might surprise your colleagues?

A band I started while at university (Oi Va Voi) went on to win a British World Music Award … without me!

What’s the best advice you ever received?

I don’t remember where this came from, but I’ve taken it as my motto – ‘choose brave’. It’s sometimes unclear what to do when making a big life decision and the only ones I’ve ever regretted are when I took the easier path. So yeah, Choose Brave!

What’s one thing that makes you happy?

Wearing goggles and floating in the calm waters of Clovelly. I can just about surf, but my favourite part is sitting on a board at the back, not surfing, and just being surrounded by water. The ocean is my happy place.

What day in your life would you like to relive?

My dad died suddenly aged 59. I was in my 20s and fiercely independent. The last day I saw him, I was about to board a plane home from Spain and I remember telling him to leave me alone so I could get going. I wish I could relive that moment, give him a big hug and allow him to be a dad.

What’s the best thing you’ve heard in the last year?

The Future of Decision Making, A Nobel Prize Dialogue held here at UNSW in October 2024. One of the speakers, Saul Perlmutter, just blew me away, giving me the first feeling of hope I’d heard in a long time. He described how universities are where we should be teaching critical thinking, empowering students to live with uncertainty and make decisions based on evidence, not binary for or against. That gave me hope.

- Log in to post comments